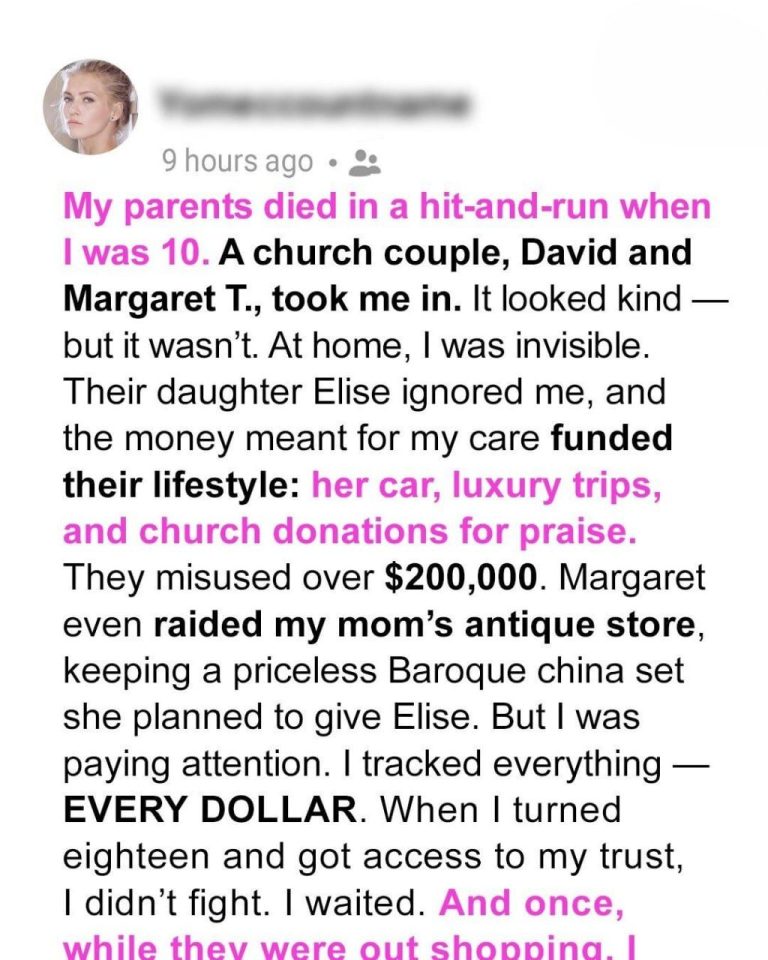

Every dollar they spent. Every new piece of furniture. Every vacation photo they proudly displayed on the mantle. Each one was a physical punch to my gut, a fresh stab to a wound that never, ever healed. They called it a blessing. They called it a blessing from God. I called it theft. And I promised myself, from the moment I understood, that I would give them exactly what they deserved.

My parents died when I was young. Too young. A terrible accident. One day they were there, vibrant and loving, the next they were gone, and I was just a shell. I ended up with their closest friends, a couple who seemed, at first, like saviors. They had no children of their own and welcomed me into their modest home with open arms. Or so it seemed.

My parents, it turned out, weren’t just loving. They were smart. They had planned. They had left a significant sum, not just for my immediate care, but specifically, explicitly, in a trust for my future. A substantial amount, enough to guarantee my education, my health, my stability. It was managed by them, my new guardians, until I came of age. They were supposed to be stewards of my future, guardians of my legacy. Instead, they became vultures.

It started subtly. A new car that was “unexpectedly on sale.” A kitchen renovation that was a “much-needed blessing.” Then came the holidays, the vacations, the sudden comfort that hadn’t been there before my parents’ passing. I was just a child, lost in grief, but I wasn’t blind. I heard hushed conversations. I saw the bank statements they carelessly left on the kitchen counter, comparing balances from before and after. The numbers didn’t lie. Their initial struggles seemed to vanish overnight, replaced by an ease that felt completely unearned. And always, always, they’d say, “God provides. This money, it’s a blessing.” My blood ran cold, even then. I understood. That wasn’t God providing. That was my parents providing. And they were taking it.

An older woman’s face | Source: Pexels

But the real betrayal, the kind that digs into your very bones and makes you question the nature of evil, came years later. I was ten, then twelve, then fourteen, living with a persistent, gnawing pain in my leg. A congenital defect that my biological parents had been aware of. It required a series of complex, expensive surgeries and years of physical therapy. This wasn’t just about comfort; it was about my ability to walk without a limp, to run, to live a normal, pain-free life. My parents had diligently saved, establishing a separate, smaller fund within the main trust, specifically for these medical procedures. This was my only hope for a normal future.