“Your turn,” she said.

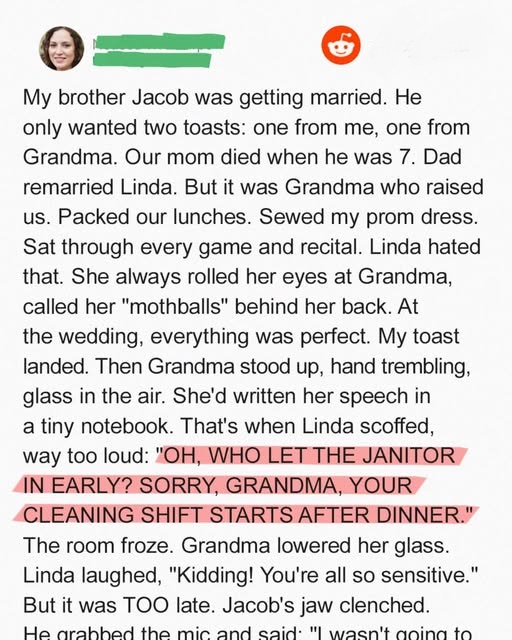

Linda stood like someone standing in a boat: careful, aware of balance. She held her glass in both hands like it might run. “I won’t be long,” she said, voice rough. She looked at Jacob. “I don’t have a speech. I usually do.” She huffed a small laugh at herself, and the room allowed it. “I was terrible to you. To you both.” She looked at Grandma, and her mouth trembled. “Mostly to you. You held it all together when the rest of us fell apart. I thought if I made you smaller I would feel bigger. I didn’t. I just made everything meaner.”

She paused, searching for something and deciding to say it even if it made her ugly. “I want to do better. Not be congratulated for it. Just… do it.”

She choked on the last word. No one clapped. No one saved her. We didn’t need to. Grandma reached out, patted the back of her hand—two light taps, like a key turning—for the exact amount of time a person can stand being comforted by someone they’ve wounded.

In the weeks after, nothing changed dramatically and everything did. Linda still cared about her nails. Grandma still ironed pillowcases—God knows why. Dad started leaving the TV on too loud and no one snapped about it. Jacob and Lila hosted Sunday dinners where people arrived at different times and left with leftovers in yogurt containers. When Linda moved a vase on the credenza three inches to the left, Grandma moved it back and Linda… let it stay there. I bought a cheap microphone and we started doing karaoke in the kitchen. Linda cannot sing. It turns out that is beside the point.

Sometimes the past still reared up like a wave and smacked us right in the face. The first Christmas after the wedding, Linda asked unthinkingly if we could “tone down the Grandma smell,” and the three of us looked at her like she’d farted in church. She closed her eyes, inhaled once, and said, “I’m sorry. That was cruel. I meant the cinnamon is too strong.” We opened a window and kept the cinnamon.

see more on the next page